Der Text erschien erstmals am 12. Dezember 2025 bei Geopolitical Intelligence Services.

The Federal Republic of Germany has experienced several examples of great leadership. In today’s perilous circumstances, the question is whether the country’s politicians are up to the task of again leading the nation, uniting a fractured society and taking the bold, perhaps uncomfortable steps necessary to ensure continued prosperity.

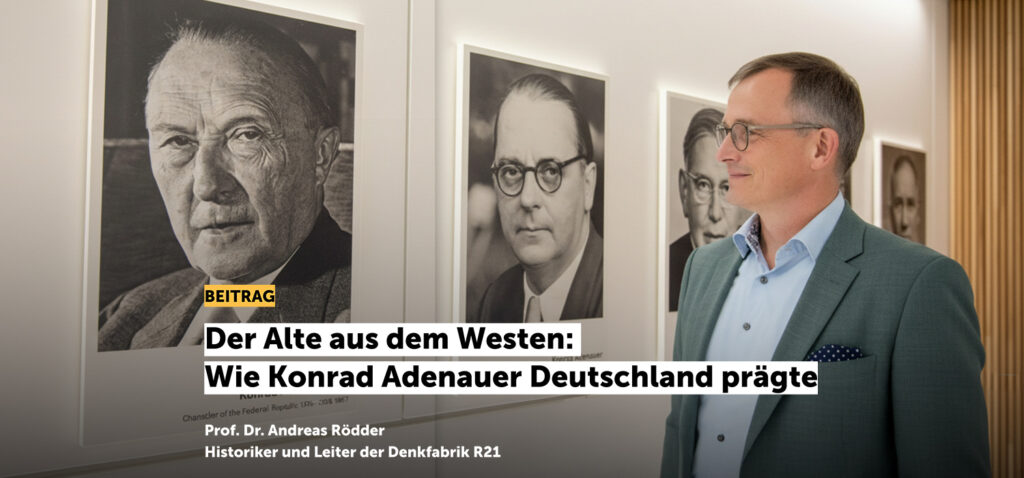

Konrad Adenauer, its founding chancellor (1949-1963), established Germany’s integration with the West and the rearmament of the country in the 1950s. That readjustment was at odds with strong pacifist attitudes after World War II, ambitions for neutrality and hopes for reunification.

The Ostpolitik of Willy Brandt (1969-1974) in the early 1970s brought together West German foreign politics with an international detente and involved the Federal Republic with the Soviet Union. He was severely criticized for these moves, which were seen as selling out the Eastern territories and abandoning the drive to unite the two Germanies.

Helmut Schmidt (1974-1982) was a driving force of the NATO double, or dual-track decision of 1979 to counter Soviet nuclear armament by the deployment of United States nuclear missiles in Europe. Schmidt lost the chancellorship due to his party’s shift to the opposing peace movement.

His successor, Helmut Kohl (1982-1998), secured the implementation of the double-track decision in 1983. It frustrated Soviet ambitions and brought about President Mikhail Gorbachev’s reform politics, which in turn led to the peaceful revolutions in Eastern Europe and the end of the Cold War. Kohl jumped at the historic chance to realize German reunification within a year. Correspondingly, he promoted European integration, leading to the Treaty of Maastricht and the introduction of the European Monetary Union, which was rather unpopular in Germany.

Finally, when Germany in the late 1990s and early 2000s found itself the “sick man of Europe,” suffering from domestic and social burdens after reunification, Kohl’s successor Gerhard Schroeder (1998-2005) accomplished the “Agenda 2010” reforms of the welfare state. They blew up his chancellorship but laid the foundations for a decade and a half of German prosperity.

Angela Merkel: Moderation without strategy

However, since the beginning of Angela Merkel’s chancellorship (2005-2021), Germany has lacked equally courageous leadership. To be sure, long-lasting decisions were taken: the handling of the global financial crisis in 2008 with the state warrant for savings; the rescue of the euro after 2010; the decision for the German nuclear phase out in 2011 and the energy transition; the building of Nord Stream 2 and the refugee policy of open borders in 2015.

Even if the latter decisions became controversial and revealed their problematic consequences in the long run, they resulted from a general consensus in the political center in their day. During the 16 years of her chancellorship, Ms. Merkel led three coalitions of the center-right Christian Democrats (CDU in most of Germany and CSU in Bavaria) with the center-left Social Democrats (SPD), originally covering 70 percent of the political spectrum. They were interrupted only by a remarkably ineffective coalition with the Liberals between 2009 and 2013. While in office, she executed core objectives of a green zeitgeist, which became dominant in the 2010s.

Chancellor Merkel’s leadership is best characterized as “moderation” in the dual sense of the word: both mediation and temperance. In the euro debt crisis, her primary goal was to keep things running and to keep Europeans together, to preserve the monetary union and to prevent a breakdown of the system. She had a strong sense for what was at stake and what was impossible or inadvisable to do. Yet she had no idea what needed to be newly created and little strategic sense for long-term perspectives.

The same was true for her politics toward Russia and Ukraine, when she mediated the Minsk II agreement to prevent the collapse of Ukraine in 2015, but failed to adopt measures to strengthen Ukraine when Russia disregarded the agreements. Instead, she pursued German-Russian special relations through North Stream 2 to secure cheap energy for Germany, though at the cost of emboldening Russia and jeopardizing Eastern European security.

These politics correlated with German economic interests. Germany under Chancellor Merkel pursued what American political scientist Stephen F. Szabo called “commercial realism” following a geopolitical triad: obtaining cheap energy from Russia, security from the U.S. and economic growth through exports to China. Benefitting from prosperous economic development and the European Central Bank’s politics of low interest rates, Chancellor Merkel’s governments were able to address worsening structural problems by spending money – particularly for German energy policies and millionfold asylum migration.

Her actions shifted the German political system. While Chancellor Merkel became increasingly popular among the political left, she drifted away from the center right and inadvertently enabled the establishment of a far-right opposition explicitly founded as an alternative to her politics. Ms. Merkel’s advisors regarded the rising Alternative for Germany (AfD) party as a tool to weaken the left by “asymmetric demobilization of voters,” to quarantine the right by an impenetrable “firewall” and to strengthen the center by shifting the Christian Democrats to the left.

This constellation allowed Chancellor Merkel to build two more governments in 2013 and 2017 – and the AfD to attract more than 20 percent of voters on the federal level and up to 40 percent in the East German states by the early 2020s. The result was a polarized society and an increasingly paralyzed party system.

Olaf Scholz: ‘Zeitenwende’ without substance

After Ms. Merkel’s second-longest tenure as chancellor in the history of the Federal Republic, Olaf Scholz’ three years and five months were among the shortest. What will be remembered of his chancellorship (2021-2025) is his famous Zeitenwende (“turning point”) speech in the Bundestag of February 27, 2022, three days after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It not only set a rhetorical landmark but also marked a cultural shift from a German self-understanding as a “civil power.” The nation went from relying on concepts of “change through trade” and “modernization partnerships,” soft power and an absence of geostrategic thinking, to an acceptance of international responsibility as a European power, including the necessity of functioning military power.

However, an overall shift of German orientation in the 2020s was not accomplished in a single moment. In an article for Foreign Affairs on “The Global Zeitenwende,” Chancellor Scholz laid out significant changes as well as continuities. He denied the existence of a bipolar world order but banked on the traditions of “dialogue and cooperation” and committed his country to a European Union that sets “global standards on trade, growth, climate change and environmental protection.” At the end of the day, Scholz’ Zeitenwende turned out a melange of cultural and military shifts, of Zivilmacht (“civil power”) continuities and a lack of material progress.

Meanwhile, worse than Ms. Merkel’s two-party coalitions, Chancellor Scholz had to balance three coalition partners: the left, the center left and the center right in the “traffic light coalition” of Social Democrats, Greens and Liberals. It started with the ambition to act as a “modernization coalition,” yet the range of goals proved too wide. The effort was particularly weakened after the Federal Constitutional Court declared its budget unconstitutional and prevented the allocation of special funds in order to placate political differences by providing money for all parties. Scholz’ government failed within less than three years without accomplishing the fundamental reforms that it had promised.

Friedrich Merz: Unfulfilled promises and political predicament

When early federal elections were scheduled for February 2025, the Christian Democrats, in the meantime led by Ms. Merkel’s old intra-party adversary Friedrich Merz, promised a policy change toward fundamental reforms of a stagnating economy and an overburdened welfare state. However, Mr. Merz had to build another centrist coalition of Christian Democrats (28.6 percent) and Social Democrats (16.4 percent), and he adopted a set of compromises instead of following liberal-conservative core values as his supporters had expected.

In borrowing her governing style, Chancellor Merz became Ms. Merkel’s heir, though with less sense for power, social relations and communication skills. He underestimated credibility as a political resource when he broke his promises and abandoned Christian Democratic principles such as the debt brake even before taking office. In late 2025, his coalition government was struggling about the necessity of undertaking economic and social reforms, yet was finding it increasingly difficult to pursue a common agenda.

On the international level, Mr. Merz has enhanced Germany’s standing and its European visibility; however, disjointed Europe is still far from a global player in international politics. At the time of writing, the Merz government has been in office for roughly seven months. Many governments struggle in their beginnings. Nevertheless, thus far in his tenure, the expectation, or rather hope, for powerful leadership has substantially decreased.

If his coalition fails, it will shatter the German political system. If a reform agenda is not possible for the CDU/CSU with the Social Democrats, a coalition of CDU/CSU with SPD and Greens (necessary for building a majority according to recent polls) would prove even less capable of acting. It would reinforce the CDU’s predicament: Making concessions to the left only strengthens the AfD on the right, while any form of cooperation with the AfD − so far marginalized by the firewall − might tear apart the center right’s crucial actor, the Christian Democrats. However, the CDU under Chancellor Merz’ leadership has refused to address this conundrum strategically.

Reasons for the crisis of leadership

Germany’s crisis of leadership is not only the result of Mr. Merz’s personality; there are at least three structural factors behind the persistent lack of substantive decisions, course corrections or sustainable reforms.

First, the political system: 20 years of centrist coalitions have prevented substantial changes of government (as had been the case in 1969, 1982 and 1998). They have led to a path-dependent continuity of compromises and micromanagement instead of fundamental debates and directional changes in the center while pushing the democratic interplay of government and opposition parties to the fringes. The result has been an increasingly immobile political center with decreasing agency under increasing pressure from the margins.

Second: polls, the media and the public. Unceasing opinion polls create a permanent stress for politicians. Communicated by the mass media, they create their own political reality and have become influential objects of daily political business. A short-termism of plebiscitary elements counteracts the principles of representative parliamentary democracy that should provide officeholders with the freedom to act for the time elected and enable them to adhere to contested decisions.

Third: political culture. Established as part of a green hegemony, moralizing counteracts a tolerance for ambiguity and ambivalence, and a desire for consensus and appreciation counteracts the readiness for controversial debates and strong decisions – both being preconditions for significant leadership.

However, since the green zeitgeist in recent years has given way to a rightward shift in Western societies, and as Germany’s political system, economy and welfare state are under severe pressure, fundamental debates and controversial decisions are likely ahead – and questions of leadership may become unavoidable.

Scenarios

Most likely: The coalition persists without accomplishing substantial reforms

The centrist coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats goes on without resolving necessary, fundamental economic and social reforms. The Social Democrats are still traumatized by Agenda 2010, which yielded prosperity for the country but was perceived as a sacrifice of social justice and thus inhibits fundamental economic and social reforms.

Meanwhile, the Christian Democrats are trapped in the current coalition because they would not achieve an alternative majority by joining forces with the Green Party and since Chancellor Merz has excluded both cooperating with the AfD or leading a minority government.

The firewall traps the Christian Democrats in a vicious cycle of making concessions to the SPD that weaken support for the CDU and strengthen the AfD. This state of affairs makes the Christian Democrats even more dependent on the left, resulting in further concessions, and so on.

Not very likely: Economic pressure the SPD to accept economic and social reforms

The centrist coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats remains in place and agrees to embark on fundamental social and economic reforms. While the Christian Democrats would be willing to do so, it would require an “Agenda 2010” moment within the SPD. In view of the intra-party realities such a constellation seems far away, however historical experience displays that pressure from a mounting economic crisis can create unexpected readiness to act.

Unlikely: CDU goes it alone

Due to a lack of agreement on basic reforms, the coalition breaks up and Chancellor Merz proceeds with a minority government of the CDU and the Christian Social Union, its Bavarian sister party, searching for majorities (including support from the AfD) on an issue-by-issue basis. Apart from his strong commitment against it, this scenario would require setting firm priorities for policy change, a strategic understanding of the CDU’s structural predicament and the fortitude to withstand a gegen rechts (“against the right”) public and media storm.

Such an act of leadership and risk-taking, like those made by great leaders from Konrad Adenauer to Gerhard Schroeder, seems feasible only in the event of unexpected and overwhelming pressure from external events and a failure of the second scenario.

More unlikely: The current coalition elects a new leader

Growing dissatisfaction with Chancellor Merz leads the existing coalition to choose his replacement by finding a candidate with better polling numbers. However, since the necessary absolute majority in the Bundestag would require votes from the SPD, and all alternative candidates in question would exclude support from the AfD, this maneuver would increase the CDU’s dependence on the Social Democrats. That would fuel the downward spiral as described in the first scenario, or, alternatively, increase dissatisfaction with consequences as described in the concluding scenario.

Impossible: The center right joins with the far right

Growing dissatisfaction with Chancellor Merz leads to his replacement by an alternative candidate from the CDU/CSU who would be elected with the support of the AfD. Apart from not being prepared in any way, this maneuver would tear apart the Christian Democrats. So, while possible in theory, in practice this is in no way feasible.

The great unknown: Fracturing of the center right

Growing dissatisfaction on the center right and tensions within the CDU lead to a split of the CDU or the founding of a new center right party somewhere between the CDU and AfD which would solicit remaining liberal voters (since the FDP fell out of the parliament in 2025), core Christian Democrats who are disppointed by Merz and moderate AfD voters ready to rejoin the center right.

Author

-

Andreas Rödder ist Leiter der Denkfabrik R21 und Professor für Neueste Geschichte an der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz. Gegenwärtig wirkt er als Helmut Schmidt Distinguished Visiting Professor an der Johns Hopkins University in Washington. Er war Fellow am Historischen Kolleg in München sowie Gastprofessor an der Brandeis University bei Boston, Mass., und an der London School of Economics. Rödder hat sechs Monographien publiziert, darunter „21.0. Eine kurze Geschichte der Gegenwart“ (2015) und „Wer hat Angst vor Deutschland? Geschichte eines europäischen Problems“ (2018), sowie die politische Streitschrift „Konservativ 21.0. Eine Agenda für Deutschland“ (2019). Andreas Rödder nimmt als Talkshowgast, Interviewpartner und Autor regelmäßig in nationalen und internationalen Medien zu gesellschaftlichen und politischen Fragen Stellung; er ist Mitglied im Vorstand der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung und Präsident der Stresemann-Gesellschaft.

Alle Beiträge ansehen